Photo by jeffmason. Image reproduced under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic License.

I was reading Margaret Atwood’s Oryx and Crake when Netflix’s revival sitcom Fuller House was released. Ever the bleak soothsayer, Atwood’s thirteen-year-old novel takes place in a bio-engineered post-apocalyptic future, an imagined land not too far from our own time. Protagonist Snowman narrates the story, detailing how he became the sole human survivor in a wasteland littered with the remnants of civilisation. Through a series of flashbacks Snowman catches the reader up to speed, recounting a time when he was known as Jimmy, conducting life in a neoliberal nightmare born of extreme corporate privatisation, technological exploitation and blatant class division. The arts are maligned; scientists are the ruling class, living in compounds of various luxury while everyday schmucks are kept in the Pleeblands ghetto.

“Students of song and dance continued to sing and dance, though the energy had gone out of these activities,” Atwood writes. “And though various older forms had dragged on—the TV sitcom, the rock video—their audience was ancient and their appeal mostly nostalgic.”

If comedy is tragedy plus time, does that mean tragedy is the comedy throwback? With the rise of the renewable franchise—an age of cheap pre-packaged content in the form of the revival TV series—somebody better cue the canned laughter.

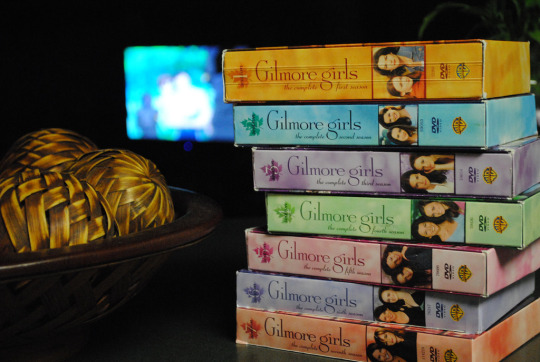

Within its very narrative construct—status quo, conflict, resolution, rinse and repeat, week after week—repetition is the mainstay of the sitcom. Returning to the same setting at the start of every episode—be it a café, study room table or family home—is as comforting and familiar as the old couch in your living room. In his detailed study Sitcom: A History in 24 Episodes, Saul Austerlitz notes how sitcoms were never meant to be studied or, beyond network-dictated syndication, rewatched. Obviously, in the age of DVD box sets, streaming services and torrents, technology has changed all of that. So here we are, frequently revisiting our old favourite shows in the same way we used to visit old friends IRL.

Just last month, New York magazine ran a cover story questioning whether Friends (1994–2004) is still “the Most Popular Show on TV?” In an article laced with his own nostalgic longing for the show, writer Adam Sternbergh explains how old fans are coming back to Central Perk while new fans, like Paulina McGowan, who was born the year Friends debuted, watch it for its depiction of glory days passed: “It would be awesome to be alive back then, when everything didn’t seem so intense. It just seemed really fun.” However, for some Friends fans—and, if my Facebook feed is anything to go by, this pertains to Gilmore Girls as well—the fact that, as Sternbergh states, Friends mined a “very different geist, in a very different Zeit,” the political implications of rewatching an old favourite is fraught with complications. Only last year, Margaret Lyons responded to a question from such a Friends fan concerned with its homophobic and fatphobic storylines. Writing for Vulture, the magazine’s entertainment news vertical, Lyons admits to loving the show but hating its queer, gender and body politics. Friends“reflected the mainstream values of its time—values that have changed, thanks to the hard work of many people.”

So why are reunion shows so popular? Recycling isn’t new to television; like film, music, literature and theatre, from Greek myths to Marvel comics (or Greek Myths in Marvel Comics), rehashing existing stories is a standard artistic trope. But why do we rewatch these sitcoms for comfort when their shortcomings make us so uncomfortable? Are viewers so scared by increased social awareness, progress and cultural diversity that, as John Doyle argued for The Globe and Mail, they’re clinging to Friends for its obvious celebration of middle-class white privilege? The current spike in revival shows like Fuller House and The X-Files and Gilmore Girls and Twin Peaks (to name but a few) would indicate, troublingly, yes.

This piece appears in full in The Lifted Brow #30. Get your copy now.

Stephanie Van Schilt is a contributing editor at The Lifted Brow, co-host of The Rereaderspodcast and freelance writer.